Barbara Deming Remembered

Maureen Brady

Excerpted from a talk given at AWP (2018)

and from a memoir by Maureen Brady, Friendship Doubles My Universe

I have been active with the Money for Women Barbara Deming Memorial Fund for over twenty years, quite a few of those years as Board President. But long before my involvement on the Board, I had the thrill of receiving an award. I remember well that day of dragging myself to the mailbox, anticipating more of those return SASEs that would likely drop me to a new low, and instead, receiving a crisp white envelope with the news that I was a recipient of a Money for Women Fund grant. I posted it up over my desk and for many, many days every time I looked up at it, I said YES! Someone believes in what I am saying! And got a rush of euphoria.

For forty-two years this fund, the only one of its kind, has given grants to feminist writers and visual artists, without missing a year. Forty–two years in which a lot has changed and yet the need to preserve spaces and support for feminist voices to be heard remains a crucial mission. We are deeply gratified to see a new range of women of all ages speak out with the Me Too movement and flood the streets in protest against the racist and zenophobic policies of the current government, but it makes our mission all the more important. Because as the poet Audre Lorde said, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

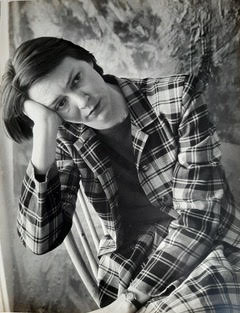

Barbara Deming, 1953. © The Imogen Cunningham Trust.

All Rights Reserved

As the years pass, fewer and fewer of us who knew Barbara Deming and what she represented remain. When I asked one younger woman what she would like to know about Barbara, she said, “To start this fund, to do something like this that we need so much more of . . .well, I’d like to know—what was she thinking?”

Barbara began the work of forming a nonprofit organization in 1975 and the first grants were made in 1977. What she started with was the statement: “I’ve been helped to do my work, so it seems right that I should help others.” She had been in a devastating automobile accident, enroute to a demonstration, in which she suffered multiple fractures and internal injuries, and she started the fund with the settlement she received for her pain and suffering. Then she went on to contribute monthly, as much as she could. She came from a family that had supported her with an annual allowance from a trust, but lived frugally and contributed whatever she had left over. She carefully established her own trust and designated a portion of it to be distributed to Money for Women each year upon her death. She implored other women to contribute as well, reminding them this money would be much better used for our benefit than dollars they would otherwise give over to our government in taxes to develop nuclear weapons and fight wars. Her partner of many years and lifelong friend, Mary Meigs, another extraordinary woman, became a major contributor, giving generously during her lifetime and leaving an annuity of $16,000 per year at the time of her death. An annuity that expired in 2017, leading us with need to amp up our fundraising efforts.

I had the great privilege of knowing Barbara Deming as a friend and mentor, and because I had that priviledge, I would like to take you back with me to let you know this exemplary person better.

I met Barbara when attending the National Women’s Studies Association Conference at U Conn in 1981, where I had been invited to do a reading. It was a particularly warm day and those of us from the north, still thawing out from winter, lay about on the grass in the sun, arms and legs akimbo (this, of course, predates Lyme disease). I was half asleep when a woman came over and whispered to me that Barbara Deming, who was propped up against a grass bank a hundred feet away, would like to meet me. I’d been noting her books for months at Womanbooks (then a fabulous feminist bookstore on Broadway in Manhattan), admiring her look on the full cover picture on one of them, and recognizing her as a force, though I hadn’t yet read the books.

On that cover, she had the most serious face I had ever seen, with more than a tinge of melancholy looking out from her solid brown eyes. Her straight brown hair was cut as if from a bucket placed over her head, bangs long and sheared off straight at eyebrow level. She looked right into you, almost too starkly. When I peeked over as inconspicuously as I could to discover that she looked exactly like that picture on her book, she caught my eye and cocked her head to indicate I should come over.

When I took her hand, she covered mine with both of hers, long bony fingers, cold despite the sun. A wool scarf was wrapped around her neck and she lay on a blanket. I would find out later she was always cold, had been ever since those injuries she’d suffered in that auto accident, the one from which she’d started the Money for Women Fund.

She told me she’d loved reading my novel Give Me Your Good Ear, and began asking about the characters, whom she seemed to know intimately. She was your ideal reader in that way. She asked about how my family had received the book, because I’d used a setting that closely resembled my family’s farm in upstate New York, but in the novel things happened that had never happened in my family. Namely, after an incident of abuse, the mother in the novel stabs the father to death while both of my parents were then still very much alive. Strangely enough, my current novel, Getaway (published in 2018), is also about a woman who stabs her abusive husband, although in the first novel the story was told from the point of view of the daughter as witness to this trauma.

As Barbara questioned me, her eyes stayed so intensely upon me that I felt lit up by them and more boldly kept my eyes on her, though, every now and then, one of us would cut away and look down at the grass in shyness. When the break time ended, most of the women grumbled about leaving the sun but moved back into the classrooms for the conference presentations, but neither Barbara nor I budged. We went on talking about various aspects of the abuse of women, Barbara speculating about women who were currently in jail for murdering their husbands, how most likely they had only done what they had done to save themselves from great injury or the loss of their own lives. She worked her way around to nonviolence, asking questions of me and of herself about how could all this be avoided. Because surely there must be a way. And surely, if we concentrated long and hard enough, we could begin to see it. This was who she was—pragmatic visionary with perseverence. She got a vision of some ideal in her mind’s eye and then teased at finding a way to make it happen. She worked from a strong central will that was almost myopic, yet made its way outward, ultimately covering a wide landscape. I fell in love with her over the next couple of hours, as we talked until the angle of the sun lowered and the dampness of the ground bled through. An hour before, Barbara had pulled this rangy looking thing up over her lanky, bony-kneed legs, so she was already wrapped in her thick wool blanket.

I found out when I read her books that she was known for her long walks—starting in 1964 with the Quebec – Washington – Guantanamo Walk for Peace and Freedom, which became a civil rights march when their bi-racial group was prohibited from marching through Albany, Georgia. Those who sat down in civil disobedience were carted off to jail, an experience from which Barbara composed her book Prison Notes, telling the stories of the group she was imprisoned with as well as analysing the flaws of the jail and the justice system. The demonstrators participated in a hunger strike, which several of the prisoners barely survived. One of them was Yvonne Klein, a woman who later became an early board member of the Money for Women Fund.

Barbara credited a trip to India in1959 with the early shaping of her politics. When she returned home she immersed herself in the writings of Gandhi. Then, in 1960, she made a trip to Cuba. She wrote, “The shock of the trip to Cuba began my liberation—the profound shock of discovering the gap that lay between what I had been told was happening there, and happening between our two countries, and what I now learned for myself was happening. …I came very rapidly to recognize myself as a radical.”

In Cuba, Barbara managed an interview with Fidel Castro by walking up to him at a public gathering, as it had been suggested she do by friendly Cubans. A group of Cubans surrounded them and listened to the conversation, then remained with her, elaborating how they felt about Castro’s Cuba for another hour after he had gone. They told her they felt safe, that his government was absolutely honest and such a thing had never happened in Cuba before. Barbara wrote: “There is a gesture in Cuba, where the speaker touches the corner of his eye, meaning, ‘I have seen it.’” Barbara had seen it—the discrepancy between what her country had told her to believe and her actual experience.

Her collection of essays, Revolution and Evolution, charts the building of and explosion of the Movement of the 60s, with the civil rights and then the peace movement and the emergence of the second wave of feminism. She also published a book of essays called We Are All Part of One Another. And her novel, A Humming Under My Feet, in the works for many years, was published posthumously. In 1985, Spinsters Ink published a new version of Prison Notes, with an intro by Grace Paley, called Prisons That Could Not Hold, containing a section on her participation in the Seneca Falls Women’s Peace Encampment and the walk for which she was jailed there in 1983.

For anyone who might want to research Barbara further, her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, where also the archives of the Money for Women Fund are held. Parts of Barbara’s life are documented in the film Silent Pioneers. And in 2011, Martin Duberman published a book called A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds.

Whenever I visited Barbara at her home in Sugarloaf Key, we talked for days solid and I observed how she worked and worked her mind at solutions. In the process of solving one problem, another would arise, which she would then take up. Everything seemed to go back to abuse and war—how to get the abuser or the war mongerer to see how he or she was hurting not only his victim but himself. Committing a crime against his own humanity. For humans were not meant to struggle to annihilate one another. She studied the natural world and would pull up examples from it, though she would gloss over examples of ‘dog eat dog’ animal behavior. She would beam good thoughts at difficult situations or people and had a real belief in these vibes getting through. When one left at the end of a visit, she would come out with a wand and bless the car you were driving—the engine, the tires, the front, back and sides—before you drove off.

She was not particularly warm when it came to emotions, yet her cerebral self was tempered by a deep spirituality. One day she walked me to a cove at the end of the next street from hers on Sugarloaf Key, and we rolled up our pants legs and waded, studying the complex life going on in the tide pool at our feet. The water had a greenish hue and when you looked up and out, it went on for as far as you could see. “I come here to watch for the great blue heron,” she said.

“I hope he’ll come, that would be super,” I said.

When I next looked up, she was standing off to my right, and her long arms dangling out to her sides had turned into wings and were rising and falling as if she were flying, as a small cooing noise escaped her lips. Her eyes were closed with concentration. She looked either like a fool, or someone so lost in her own reverence you had no choice but to revere it.

I scanned the sky and the coastline for a blue heron but saw only sandpipers. She still had her eyes closed and was cranking her arms up and down so that she did look remarkably birdlike. And then she stopped and took back up where she had left off, talking through whatever problem we had been trying to solve. We sifted and sorted through shells, looking for sundials, and then she decided she was ready to go home for her afternoon nap and I said I’d stay on a little longer. No sooner had she disappeared down a narrow path, when the great blue heron landed just about where she’d been standing. The bird folded her great wings and stood staring at me. You better believe I didn’t move for the next minute or so, though I wanted to call Barbara to come back, but I knew it was too late for her. I was having a particularly difficult time over a break up that year, and it finally occurred to me that she’d called this bird for me. I stayed still with the bird for a full minute, maybe two, before it spread its wide wings, and with one current of the breeze, lifted off sideways, rose high into the sky and drifted beyond the bend. I moved over to Barbara’s spot and tried lifting my arms the way she had, communing in my mind with a simple mantra: Come back, Peter, come back, Paul, the way my grandmother used to sing the crow song to me as a child, but when I opened my eyes there were only the sandpipers again. When I went back to the house to tell Barbara of her success, she seemed to have known it already, making her special powers all the more convincing.

Occasionally I exchanged some work in progress with her, but in keeping with her philosophical bent to find the best in everyone, she was not a particularly astute or forceful critic and her own work suffered as a result. One could see things that should be ruthlessly cut, but she would get a pained expression on her face at the word ‘cut’, as if this were repugnant to a nonviolence resistance fighter. Nor did she like to pull weeds in the garden. She didn’t like the classification that downgraded a weed so that next to it a stalk that would later produce a broccoli plant would get to live a full life whereas the weed would get plucked before it reached maturity. This worked against her in her later life when she received treatment for cancer, from which she died in August of 1984.

I visited her once when she was staying at her brother’s, being treated at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. She sat up stiffly on the side of the day bed, her head bald from the chemo, her eyes even larger than usual and more melancholy. She told me about her chemo, how she’d felt it streaming into her and wanted to welcome it, but didn’t seem able to get beyond its invasiveness. “I’m trying to visualize,” she said, haltingly, “the poison of the chemo drugs going after the cancer cells but leaving the rest of me intact. But it’s hard for me to visualize trying to kill anything.” Here was the nonviolent resister again, the woman who didn’t like to pull weeds, even if it would create more abundance in her garden.

Today, we are living in times that demand perseverance. In Prison Notes, after an absurb trial, when the truth was being manipulated to keep Barbara and her cohorts from being treated fairly, she ends the chapter, saying: “Here we sit, (meaning back in the jail cell) and here I persist in thinking: The truth cannot be manipulated as simply as that. The power we have seen displayed is based on lies, and so we can prevail against it if we are stubborn.”

Stubborness as a strategy; that seems like something we must use now in our current horrendous situation. That and her belief that we are all part of one another and must continue to search for the places where we can touch each other.

I read, just after the death of Ursula LeGuin, that Ursula said, “The values of patriarchy are buried in the very plots of our stories. New plots are needed.” Ursula was a sterling example of someone who created new plots. Barbara Deming, too, created a new plot—a very simple one—when she said that since she had been helped in her writing, it was of great importance that she help others. And then she stepped up to do so with every dollar she could muster. My hope is that you, too, will help us continue to carry forth her vision, whether with contributions or by volunteering your time and effort.

© Maureen Brady